Martha Gellhorn (Hemingway)

Banner image c. Vogue (Lee Miller, London, photographer).

Dr. Hilary Justice (JFK Library). Updated 11/2023.

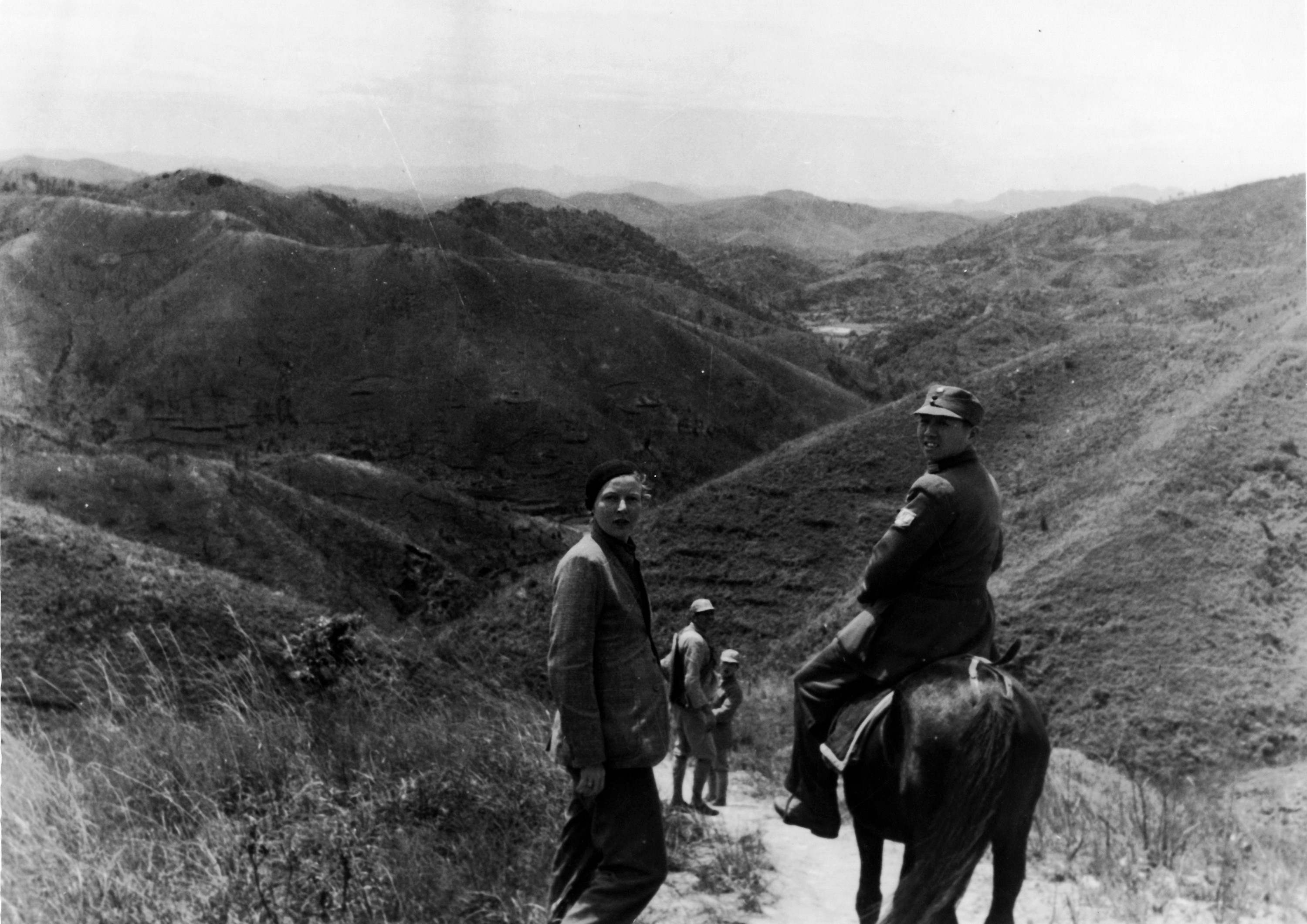

In 1936, Hemingway’s love for Spain, its culture, and its people had him following the developing Spanish Civil War with an increasingly troubled soul. Late that year, he met established journalist and war correspondent Martha Gellhorn (1908-1998) in Key West; they agreed to work together to get to Spain. His literary career in the 1930s seemed to be ebbing (critics were saying “permanently”). And although he certainly benefited from Pauline’s family resources, that also must have chafed. His journalism career, now existing in part because of his famous name, was ongoing; covering the Spanish Civil War thus seemed a good idea in many ways.

Gellhorn, who is now considered one of the finest war correspondents of the 20th century, was in every way a spur to Hemingway’s ambitions. Where he feared he was growing comfortable and soft, she was a strong individual who seemed to seek out discomfort. Where he was approaching his middle years, she seemed vital and vigorous. Whether or not they were already romantically involved before they left for Spain remains a question, as thoughts and feelings happen before they appear on paper; in any case, their relationship ignited while abroad.

Hemingway remained with his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer, until 1939, during which time his relationship with Martha intensified, in part because she seemed elusive, traveling frequently on high-profile assignments, covering increasing political turmoil in Europe. She was equal parts glamorous, athletic, and adventurous, all of which Hemingway found extremely attractive.

When they returned from Spain, they lived together openly in Cuba, renting the Finca Vigia (loosely translated "Lookout Farm") in San Francisco de Paula, just outside of Havana. They traveled extensively throughout the American West, working on their writing and embracing the sporting life in the company of wealthy friends, many of whom were celebrities in their own right. After Ernest's divorce from Pauline was final (November 4, 1940), they married (November 21, 1940) and bought the Finca Vigia outright (December 28, 1940).

Martha seemed to fit seamlessly into Hemingway's preferred lifestyle. She enjoyed spending time with his children, who participated enthusiastically in their father's outdoor pastimes. (Jack and Patrick's passion for the outdoors and nature conservancy informed their later careers; Jack ran the Nature Conservancy from his father's last home in Idaho, and Patrick has worked tirelessly on issues of land stewardship in the U.S. and abroad, especially Africa.)

We loved Marty. She was so much fun.

– Patrick Hemingway

For a time, Ernest's and Martha's careers ran companionably alongside. Evenings, wherever they were, were devoted to writing—Ernest on For Whom the Bell Tolls, Martha on her own fiction.

Martha Gellhorn's experiences with Ernest Hemingway in wartime Spain (and perhaps her long absences from him afterward) were fundamental to his novel For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940), which he dedicated to her. She lends her appearance to Maria, and her strength, toughness, and fierce loyalty and commitment to both Maria and Pilar. (Pilar, a composite character, also owes much to Gertrude Stein.)

The sale of the movie rights to For Whom the Bell Tolls in 1940 marked the first time in Hemingway’s career that his literary income was sufficient to live on, even given his many dependents (his children and members of his family of origin, including his mother). He no longer needed to supplement his income from publishing by working as a journalist and relying on wealthy relatives-by-marriage (especially Pauline's uncle, Gustavus (Gus) Pfeiffer). Even given the high-profile lifestyle he'd enjoyed since marrying Pauline in 1927, his own income was finally sufficient to meet it.

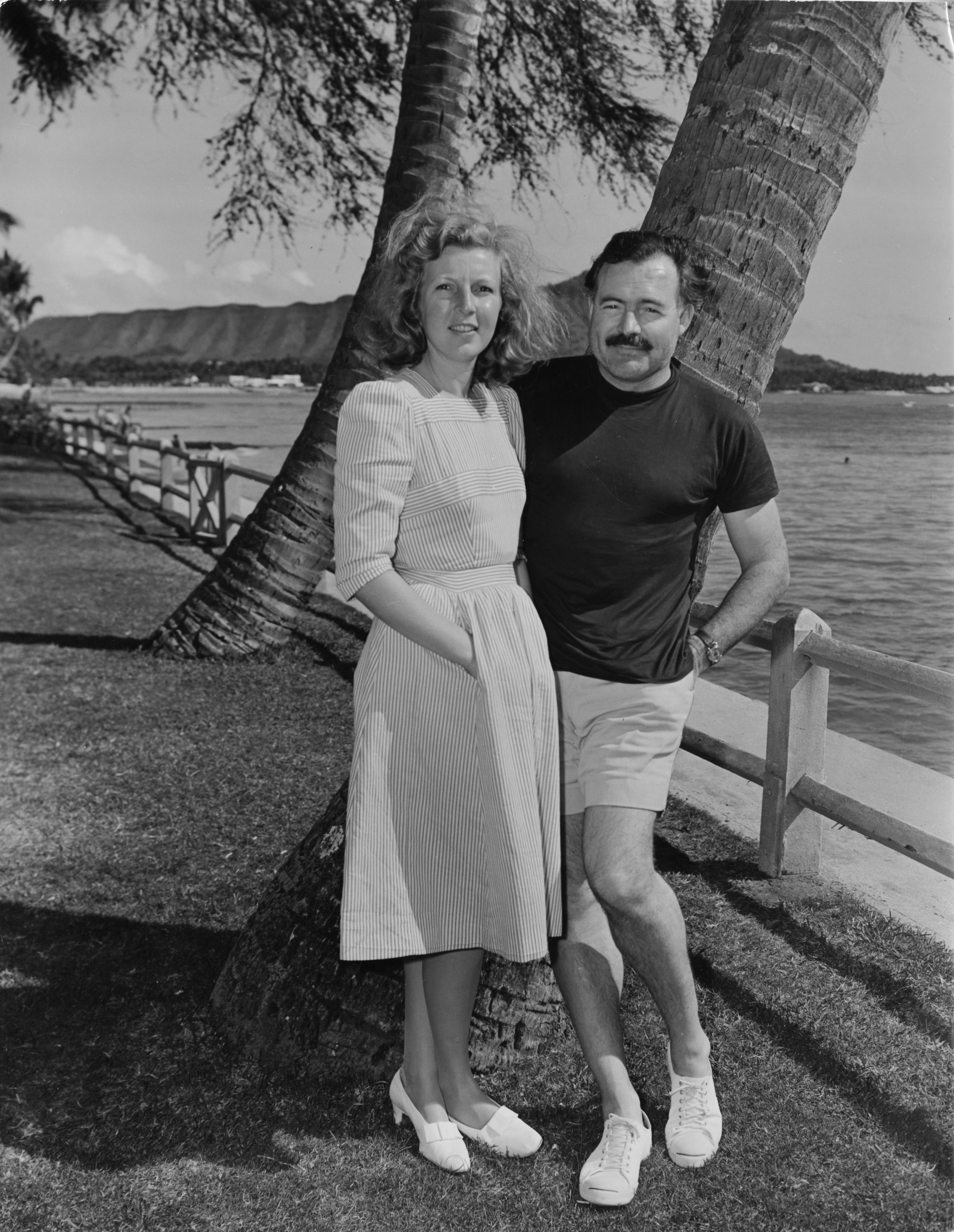

Not long after their marriage, the publication of For Whom the Bell Tolls, Martha's completion of The Heart of Another, and the purchase of the Finca, Martha Gellhorn's contract with Collier's magazine to cover the Sino-Japanese war had the Hemingways traveling together to China, with a layover in Hawaii. Although both their stars, already luminous, were on the rise, for the first time in his life, his career wasn't setting the map; his wife's was.

Of the many roles Martha Gellhorn fulfilled in her lifetime—writer, war correspondent, outdoorswoman, athlete, celebrity, even stepmother—the only one she never fully integrated was "Mrs. Hemingway."

Her ever-rising star and dauntless pursuit of her journalistic calling sparked a darker side of Ernest Hemingway: his competitiveness and his insecurity. The combination proved disastrous to their relationship. During the build-up to D-Day (June 6, 1944), Martha informed him she was leaving for Europe to cover the war for Collier’s magazine. He did not want to go, perhaps because he did not want to relive past trauma in what would be his third war (or fourth, counting his brief trip to accompany Martha to China), but when it became clear he couldn’t convince her to stay with him in Cuba, he offered his own services as war correspondent to the very same magazine.

As he must have known it would, his fame won out. He received a contract.

Martha Gellhorn was justifiably furious.

Journalists were prohibited from crossing the English Channel on D-Day. Ernest Hemingway obeyed this restriction. Although he did get a glimpse of the beach from the Channel, he delayed his landing until the next day. But Martha snuck aboard a medical ship, hid in a closet, and arrived in Normandy only hours after the battle, giving her first-hand experience of its aftermath. Check. But when their D-Day pieces appeared in Collier’s, Ernest's was the cover story. Check mate. The marriage was over.

In 2008, the U.S. Postal Service issued a series of stamps marking contributions of five 20th-century journalists: "Working in radio, television, or print, the journalists reported—often at great personal sacrifice—some of the most important stories of the 20th century. They did their part to keep people informed about the world around them."

Martha Gellhorn was the only woman among the five.